SIR Rebekkah Holylove : A Funk Lesson in Solitude

At sixteen Luther Vandross founded and served as the official president of a famous diva’s fan club. I can see him now, watching her seasoned shoulder bounce and measuring the funk in the black church two-step she makes across soul music platforms. He’s standing stage left, holding onto the curtain for balance. He’s lip syncing every song, calculating the mastery of her diction and phrasing. He’s studying her like a text; setting the stage for his own practice—one that would place him at microphones behind David Bowie, Chaka Khan, Barbra Streisand, Bette Midler and Donna Summer. He was Twenty Feet from Stardom and rising. Luther Vandross, the teenage boy, understood how Patricia Holt-Edwards from Philadelphia, became the legendary kick-your-shoes-off and snatch-your-own-wig when the tension builds between audience, music and voice; Luther Vandross presided over the fan club of Queen Motha Patti Labelle.

Strange things happen when an artist is moved to a new depth by another; we become fanatical about the fantastical beings who place us deeper into the abyss of craft. The management of details of who these artists are and how they come to being becomes a rite of passage. We obsess over the decisions they make to bring an album to fruition and take pride in knowing all things, from the major to the mundane; collaborations, music video direction, hair color, shoe size, inspiration behind the lyrics. We fancy ourselves experts of our muses. And when it comes to black music, the stakes are higher—people stay questioning our responses to the brilliance of black artists; reading them as tribal reactions, as opposed to a focused study of mastery. But no. I’m from the school of Luther—committed to scholarship, research questions and methodology when pursuing the legends.

photo by: D Todd

There’s a strong chance that I became the unofficial president of Joi’s fan club twenty-five years ago. For twenty-five years, I’ve paid attention to her musical movement. Today, I feel confident that if asked to build a theoretical framework around the genius of her crunk-funk sound, I’d have my fucking PhD. Dr. DJ Lynnée Denise.

She’s a beast.

Joi occupies space in the lineage of artists who thrive across genre lines. How is that possible? Ask Prince, Ask Aretha, Ask Nina. Ask Stevie. Black people live hyphenated lives, so it’s fair to say our musicians embody and shift the context of what DuBois called “Double Consciousness,” musical cross pollination made available to the Souls of Black Folk.

The three of us—Joi, DuBois and myself—have something in common: Nashville.

I saw Joi for the first time while I was sitting in the living room with a group of artists I met during my freshmen year at Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. She was in a straightjacket hanging on a meat hook in a blue lit walk-in meat refrigerator squirming with hopes of being released. The video was for the song “Sunshine in the Rain,” her first single. I’ve not turned away since.

Joe Gilliam

DuBois graduated from Fisk in 1888, 109 years before me. Joi is the daughter of legendary NFL football player Joe Gilliam. She was a legacy student at the historically black public university Tennessee State on Nashville’s Jefferson Street. The intersections of our lives and the black excellence it carries spans centuries.

The artists in the room knew who she was and dismissed my awe with, “oh that’s Joi.” I was in her hometown. She was their hero. “Joi from down here” they said with regional pride from blunt stained lips, “she been on that different shit for years.” I took that to mean Joi was ahead of her time and an inspiration to the folks who watched her take shape.

I copped her debut album The Pendulum Vibe (1993) and listened to it nonstop for a good year. It filled the void created by LaFace’s TLC and the Sean Puffy girl group hip-hop soul phase. Don’t get me wrong, I fucked with Mary J Blige from day one and still do, but had real questions about the war on originality that was creeping into the black musical lexicon in a Bad Boy kinda way.

The Pendulum Vibe, ironically produced by the mind behind TLC—Dallas Austin, was a game changer, a call to arms for folks looking for sophisticated melodies and enough lyrical depth to drown in. Songs like Fatal Lovesick Journey had me pondering co-dependent relationships while puffing Black & Milds and drinking Alizé. There was well-placed wailing, playful and unapologetic sexual confidence and a genre defying southern rooted sound. Anti-formulaic, the music from this album spoke to my heart and gave me hope that Black America had something to compare to the brilliant UK Soul coming out of London and coming from my speakers. Though raunchier in her approach, Joi was in the Mica Paris and Caron Wheeler category for me. My ears recognized her as a kindred spirit. After the fiftieth listen of the Pendulum Vibe I sat myself down and said with all honesty, "this a bad bitch and the masses ain’t gon’ understand," hence her long-term relationship with the abstract term, the underground.

I'm torn.

Ever since I can remember I’ve been one of those people who rolls my eyes when I hear my favorite song from a new album I'm spending time with being played on the radio. I'm suspicious of what becomes widely accepted; afraid to see the artists I love hand over their authenticity to the police of mediocrity guarding the door of pop music in America. And yeah, everybody gotta eat, but why eating gotta equate to contractual agreements that alter your purpose? Prince’s decision to pen the word slave on his face in the 90s gave us an idea of what can happen when sitting down at the negotiating table with corporations who measure your worth by your marketability to an underdeveloped and musically ahistorical masses. I wanted to keep Joi underground where she was protected from the fuckery—following her own north star to musical freedom.

Her performances embodied all the funkiness my little soul had been waiting for at a time when black radio was pinned under the thumb of payola. She’s cut from the same cloth as Hendrix. Betty Davis. Vanity. One minute she gives you seasoned performer on a FunkJazzKafe stage alongside Too Short; then range and multi-dimensionality on stage with FishBone and De La Soul the next. Embedded in her vocal chords is a deep knowledge of Funkentelechy and Parliamentarian Cosmology, a heavy load of legacy to carry, but she’s bout it and lives inside the mashup.

Between 1996 and 2006, Joi recorded three more studio albums Amoeba Cleansing Syndrome (1997), a highly desired cult classic shelved before release due to the collapse of EMI; it was then picked up by Freeworld (Dallas Austin's newly formed label in response EMI's collapse). Freeworld folded shortly after. Fortunately, it can now be purchased through her website, a gift for fans who were diggin’ through the crates in search of a copy. Her next two albums were 2002's Star Kitty’s Revenge (Crazyworld) and 2006's Tennessee Slim is the Bomb on Raphael Sadiq's Pookie Records. The music industry's instability led to Joi re-issuing the albums independently.

Joi had a major hand in shaping the Atlanta Dungeon Family/Organized Noize sound; she sang background on Goodie Mob’s classic first album Soul Food; she worked closely with many artists, among them George Clinton, Sleepy Brown, Big Krit, 2 Chainz, Queen Latifah, and Tricky from London; she collaborated with Raphael Sadiq’s on his Lucy Pearl project. In addition to studio collaboration, she joined Outkast on their final tour in 2014 and became a backing vocal for D’Angelo during his Black Messiah Tour in 2015. And still, with curriculum vitaé in hand, Joi found time to help, as she would say, “wipe down,” a few aspiring singers through her artist development business.

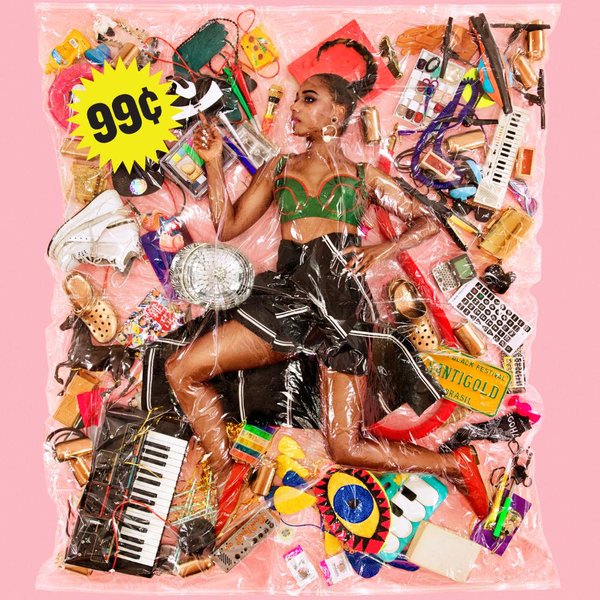

Upon moving to Los Angeles, after a twenty-year stint in Atlanta, she sat her ass down in a studio and pulled diamonds from a year of solitude to create a new gem of an album. S.I.R. Rebekkah Holylove.

But don’t call it a comeback.

There’s a white-supremacist-mean-spirited-anti-intellectual-creamsicle-looking-fuckboy in the white house. I applaud anyone who can navigate this political shit show and turn away from social media long enough to concentrate on their respective practices. I live for the kind of high art that can offer the world a break from this reality fiction, and for these reasons and more Joi came through. The journey of the album begins with three words that pushes us to the other side.

“Bitch I’m Free”

S.I.R. Rebekkah Holylove is what happens when anticipation meets expectations. Noteworthy is that this album, too, was produced independently in the spirit of Prince. He was one of the first artists to sell an album exclusively through a website because “Record company people are shady.”

Living liner notes are positioned between each track giving us poetic reflections that contextualize the song that follows or precedes it. Everything we need to move through the world of this album is provided, including a video for “Stare at Me” produced by Adam Tillman Younge of Passerine Productions and directed by Bruce Coles, and a cinematic vignette directed by Rahsaan Patterson.

photo by Rahsaan Patterson

Joi’s is the only voice on the album. Don’t be fooled into thinking that there are three fellow bad bitches in the studio making it happen. It’s just her. She writes all the album’s lyrics, arranges all its vocals, and produces some of the tracks. She uses very little of the vocal compressor, an effect that most contemporary singers rely on, creating distance between authenticity and the voices you think you love.

I had a chance to spend some time with Joi in her studio, a live/work space she calls “The Funky Jewelry Box.” Inspirational posters and album covers drape the walls from Dolly Parton to Led Zepplin and Natalie Cole to Minnie Ripperton. It’s an incubator for critical artistic thought up in there.

As I settled and began to think about questions that would unlock the door to the mysteries of this project, she was unwrapping detox products from Dr. Sebi that Erykah Badu sent her. “It’s a perfect time to fast,” she says, while removing the bubble wrap from a dark brown bottle of bodily goodness. She’s sitting at her recording station in an electric blue velvet cushioned vintage chair, “a rare find from a spot in LA,” she brags “undiscovered by hipsters and still affordable in its dealings.” The chair is perfect for the matriarchal themed nature of this album. Above her is a classic studio microphone that looks committed to its job and familiar with the racy nature of her spirit. There’s an intimacy between the two. We agree to listen to the album. She presses play and guides me through the sonic journey—joint in hand, ears on guard.

Enjoy a few selections from our session:

“Ruler,” the album’s opening track sets an important tone. It’s a theme song straight out of The Wiz; a Glinda the Good witch anthem for women who understand the magic they walk with; Not Black Girl Magic, but Black Magic Women and their dominion over the proverbial Oz. Mind the distinction. Produced by Brook D’ Leux, Joi describes the song as a “declaration and celebration of the historical facts, a firm reminder of the greatness of women.” It’s a timely tune given the national dialogue concerning the crumbling of patriarchal-powered privilege. At the same time “Ruler” avoids being reactionary and trendy, there are no hashtags connected to this reckoning. The chorus is a command: “It's a never-ending, pitch black, goddess situation/Pussy power, life giving, matriarchy, salvation.” Period.

Joi takes the lead production credit in the song “Berlin,” and invites us inside the mind of a wanderluster fantasizing about a life alongside the people of Germany. While many artists fixate on cities like Paris and London, Joi paints a different kind of dance with a country rarely explored as a destination for aspiring Black American expatriates. “I’m on my way to Berlin, I hear it’s my kind of town.” She places herself under the light of a Berlin moon drinking a vintage glass of wine, but like a true gypsy spirit never commits to the place. “I want to call it home sometimes.” The song was written while Joi was getting her bearings in California. She uses the lyrics to negotiate a plan of action giving herself two years to make it happen, and when it does, the people of Berlin will know she’s arrived as an ATLien “Givin the Deutschland something they’ve never seen…High Priestess Funk Supreme.” Bopping her head from the blue chair she says “Berlin is one of my landing pads on the planet, it’s still on my mind and manifesting itself. The song is a call out to a future site.”

Joi’s racy songs have a long-standing history. On previous albums “Narcissica Cutie Pie” (Pendulum Vibe), explores sexual fluidity and bright dark fantasies about the spectrum of desire, while songs like “Lick” (Star Kitty’s Revenge) and “Dirty Mind” (Amoeba Cleansing Syndrome) help us hold the power of sex as a powerful tool that embodies Uses of the Erotic. Sir Rebekah HolyLove builds on Joi’s collection of sex positive cantatas with “The Edge” produced and arranged by Joi with additional editing by Brook D’ Leux. A bass heavy funk monster that promises listeners a key to cities where “We can fuck until the dawn, making love til cherries gone”. I mean, yeah you’re married boo, but this is a acomplicated situation, the song implies. Cheating could become an option if good dick [or fill in the blank] is involved, and not many of us are willing to share that kind of ethical vulnerability on wax. And I don’t mean no disrespect to your official union, she asserts, but “you fuck me right and you’re mine tonight.” We never once forget that Joi is a human being dealing with the most undesirable and the most pleasurably outrageous scenarios that life asks us to consider; infidelity, heartbreak, orgasmic accomplishments. But the appeal is that she’s aware of the costs; “I’m standing on the edge with you/so if I jump will I fall or fly?”

In the song “Kush,” written and arranged by Joi and produced by Organized Noize, we get another low bass 808 banger. This time about a woman and her healing herbs, and what it means to pass one with a person you know good-and-well you’ll be taking home that night. Smoking as a form of foreplay is under-discussed. High sex deserves a love song and she delivers.

Far from insane to the membrane Cypress Hill or Snoop Dog indo smoke antics, we get reminded of the overlooked relationship that women have with a strain of weed that finds home in our exhale. Both Joi and Rihanna manage to pull off their relationships to weed well. It’s tastefully performative, radically unladylike and part of the pleasure in her solitude.

“Kingless” is a soundtrack for heart work and not surprisingly, the last song. Reflective and heavy with confession, admission and surrender. Produced by Joi, it gives us space to imagine what it might feel like to return home alone with all your matriarchal musings, global adventures and funk fantasies without a mate to share it with. What does partnership look like for a rooted funk star? How does confidence read to potential companions who may or may not have received the necessary training one might need to be the queen’s match? Nevertheless, the desire (without desperation), to walk through the world with a lover is palpable. “Kingless” is the album’s only song that can be categorized as a ballad, should you feel compelled to pin it down to a style. But I heard it as a place of departure, a new turn on an old road. A shift in the spirit of the project, a bookend to a shelf of emotionally intelligent literature in song. And she asks very simply, who can match my royalty? Who can be my peer in love? My friend? Her answer; “Not a prince half grown”.

The song “Stare at Me” produced by Joi and Brook D’ Leau enjoyed an early release as a music video, but it strikes an important chord. I hear the song as a public health announcement about the egoist and narcissist nature of social media. She describes the song’s intent as representing “The multi-layeredness of wanting to be seen and of wanting to be left the fuck alone, also wanting to control the way you’re seen.” Social Media has created a kind of “hand-held seduction, hijacking my point of view.” Everybody’s watching she says “and I wish I didn’t care, I want to care less, but I want to be on your mind.” The video and the lyrics do the sentiment justice, there’s a visual narrative reinforcing selfie culture and the unwillingness to think through the nuances of big issues that’s shaping how we all relate. Instead, we get our opinions “hijacked” and find ourselves following the wave of the crowd. She also takes on cancellation culture, insisting that politics of disposability are dangerous because "evolution is eternal." Musically, “Stare at Me” is so well constructed; pauses and spaces, kick drums and lyrics dance through the bars.

S.I.R. Rebekkah Holylove is a tribute to an album culture long forgotten. With the push for iTunes singles and music streaming culture, the intimate relating of album between artist and audience has been compromised. The album holds its own against a culture that produces music at a rate almost impossible to enjoy, I’ll be listening to S.I.R. Rebekkah Holylove for years to come and “The Pendulum Vibe” brought me here years ago. Joi says she drew from various experiences to produce this album and she’s continued to work on other major projects (both in television and music), without compromising the integrity of her solo work. In her words “I have one of the most peaceful lives than anyone I know, but I recognize that solitude and peace is something I earned and it was necessary for this particular juncture.”

Writing this piece felt like that time when Patti Labelle, and a fully established Grammy awarded Luther Vandross, shared a stage one glorious night in 1985. It’s that moment when student, fan, and gatekeeper of the musical masters graduate into a league of their own, with a platform to articulate the many ways they’ve been shaped; a tribe of fellow artists marked by the legends. And because Joi’s work has been canonized by a global community, my work to unpack her work is really a citational practice. S.I.R. Rebekkah Holylove, is on a Black Atlantic continuum—a fantastic voyage will be had. Catch up on your future.